Information — in the form of data — usually stored as binary 1s and 0s in an electronic data store, is not immutable.

Even the hardiest data storage designed to last for a thousand years, etched cleverly into some physical material, is prone to data loss. As we have seen over the past few months with so-called non-fungible data, the records that track them are stored in relational databases, which by their very nature are transient. Relational databases are designed to make it easy to perform data modifications. Even those companies in the tech industry who are making inroads into immutable data stores, like cloud vendors and storage hardware vendors, are always at risk from what an MVP I know likes to call “DROP DATABASE.” Or in my case in the mid-2000s, “drop physical server.”

In other words, you can come up with the best way to prevent data modification from taking place (and etching some resilient metal or stone with frickin’ laser beams is a pretty darn good way), but it doesn’t prevent that data from disappearing through accidental or intentional data loss.

This is not a post about NFTs, but they are an obvious talking point in the world of immutable data, so let me address them quickly with the scepticism they deserve.

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs), aside from being a scam to take away money from people who can’t afford to lose it, are predicated on the idea that some “decentralized block chain” is resilient and trustworthy, and some or other marketing fluff. This is impossible. As evidenced by recent events, no they’re not. Imaginary money remains imaginary. Eventually graphics cards or electricity or interest from investors runs out. Data corruption is insidious that way, and I’ve seen some bizarre ways that it presents itself.

The Internet, such as we could call the loosely coupled network of networks founded on the back of US military defence research, is in its middle age. The World Wide Web, invented in the late 1980s, and ushering in the growth of apps and smartphones and Apple’s success, is relatively modern in human history and yet it is already a tattered memory of what could have been. The notion of freely available data was a pipe dream as it turns out. Not only are there vast paywalls around “social” properties like Facebook and Twitter (where the currency is privacy as opposed to money), but without attempts like the Internet Archive, we have lost literally billions of pages of information. Archival from data preservationists has managed to keep the early history of the Web (like GeoCities for example), but it’s a dire situation. There’s almost nothing left of the time before 2001, which means over a decade of our history that is just gone. Even in 2022, nothing is preventing hosting providers from deleting virtual servers and purging their backups when someone doesn’t pay their bill. When people die, their digital history can be almost entirely obliterated. Maybe Facebook with their heavily compressed and monetized photo library of a dead person could be considered an archive, but there are billions of us not on Facebook.

Sadly, it always comes back to money. What is “worth” saving? Every year Wikipedia keeps asking me for money. Every year the Internet Archive asks me for money. If I don’t donate, I know that the chance of them continuing lessens each time.

We talk in the database world of testing your backups, of making sure that your recovery time and recovery point objectives are well-documented, but realistically speaking we should be doing the same for our personal data as well.

I was consulting for a startup a few years ago which failed due to lack of funding (money, always money), that would have given regular people like you and me a place to store our stuff for future generations. It was going to work in the same way that 1Password does, where instead of just passwords you could store your photos, documents, financial information, and so on, so that when you die your legacy lives on. Your estate would have half the unlock key, your lawyer would have the other half, and your legacy would be preserved in read-only mode for as long as the startup could afford to keep it. After all, data is not immutable. At some point even Facebook won’t be able to afford the costs of data storage and will be shut down.

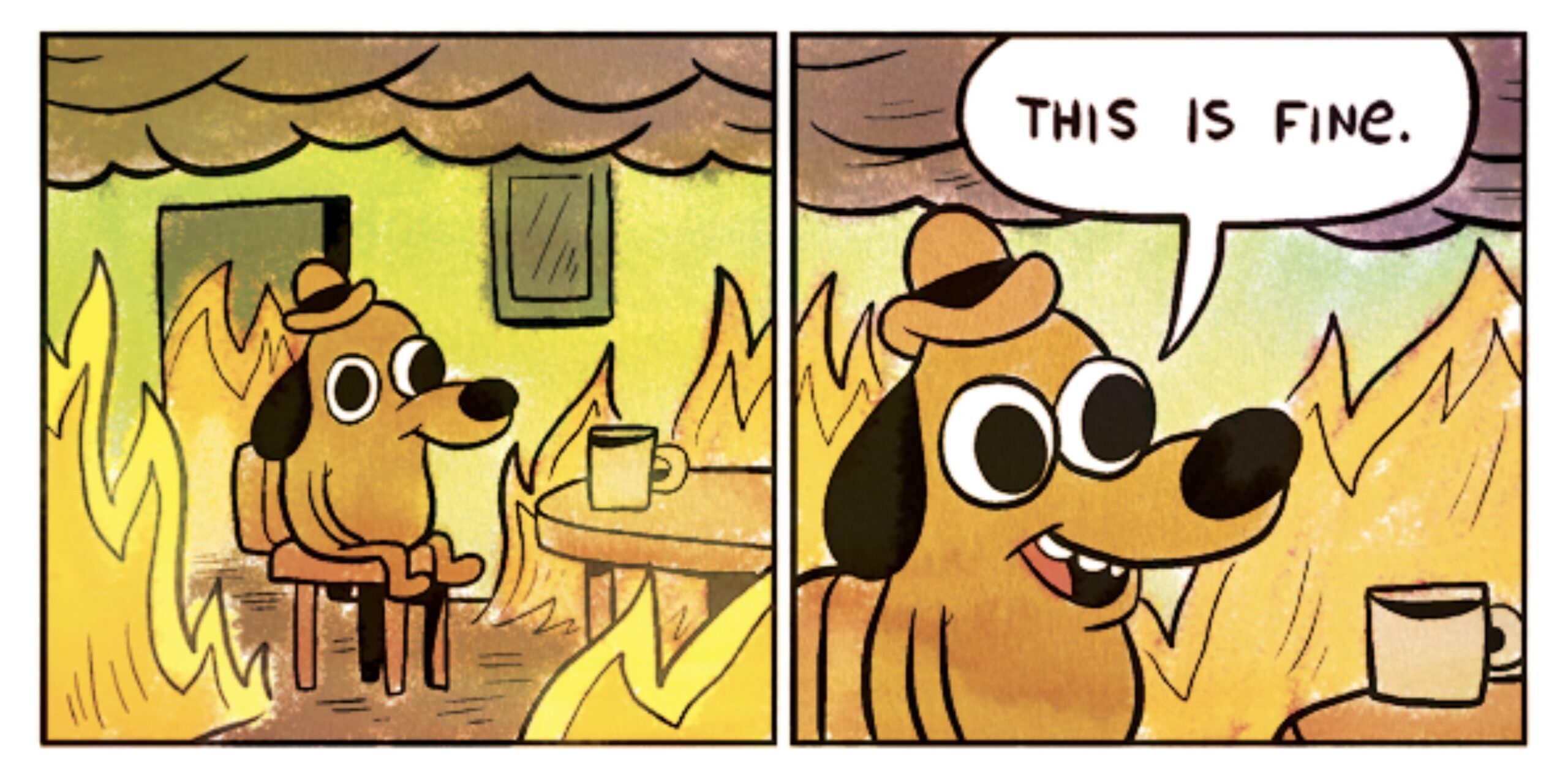

My heart cries for this future: the inevitable digital fire of the Library at Alexandria. And there is nothing we can do about it.

(Image taken from a comic strip by KC Green. All rights reserved.)

This really has me thinking. Right now, my mother is living her last few days. When she’s gone (don’t think don’t think don’t think) we still have all the old photos in a box at my sister’s house, and some degraded slides from the 1960’s. I have a few small items that she gave me a few years ago when she went into a nursing home. I don’t have a single hard-copy photo of her, though, for the past 10+ years. I realise your post is about much longer-term storage for humanity, not even just one culture, but I need my mother’s image to live on at least during my lifetime. This is a wake-up call to get some photos or photo books printed.

Comments are closed.