Choosing the right typeface for your presentation (or for that matter anything you create that contains words) is fraught.

In a previous post I wrote about the difference between serif and sans-serif. I mentioned font families, line spacing, and kerning. I also discussed why it’s important for a font to differentiate between characters that look the same. In other posts I’ve mentioned things like colour contrast, and that it’s easier to read dark text on a light background, irrespective of the growing preference for dark mode.

You need to start with the right font for the type of information you are about to convey. Depending on your background and cultural influences you may prefer a serif font, but I would hazard a guess that sans-serif is far more popular, especially if you are using a computer to do your design.

Yes, I’m calling it a design. Whether you consider it or not, every stroke of every letter or number — even punctuation — can make or break the ability of your audience to understand what you’re presenting. Everything you do that will be presented to another person is a design. There are guidelines that you may follow without realizing it. The default font sizes and styles in Microsoft Office products, for example, were designed to be good enough for most common usage. This post is going to point out some things to consider when you’re designing text for human consumption, with a focus on technical presentations because that’s the theme of this series.

So, serif or sans-serif is your first choice, and more often than not it will be sans-serif. Unless you are making a statement, you want your font to “get out of the way” of what you’re saying. People don’t recognize whole words, they read every single letter in every single word even if it happens really quickly, and as reading requires a significant mental load, when you put a lot of words on a slide your audience won’t be listening to you. Some people read really fast (including me), but it doesn’t mean they use fewer resources, and you can’t assume your audience is fluent in the language in which you’re presenting. Heck, you might even be presenting in a second or third language.

If you’re presenting new concepts, you’ll want to make sure that the font is easy to read from a distance. Many aspects can affect legibility, especially in the current virtual conference space with dynamic screen resolutions and dodgy Wi-Fi.

Once you’ve picked your font, you want to pick two or three sizes and weights. Normal text like the words you read in a book would be considered a “regular” font weight. Headings are usually a heavier weight, often described as bold or semi-bold. The strokes in each character are slightly thicker and combined with a larger size makes them a good choice for headings. However, when it comes to slides your headings just aren’t that important. You want to direct attention to certain words or phrases. Those are the words that should be bigger — maybe even bolder — than your heading. We tend to replicate professional writing techniques when it comes to slide design, and that’s a habit we all need to break.

Style, size, weight. So far, so good. Now let’s pick a font that is accessible.

I’m going to share a couple of interesting typefaces for you to consider using in the future. The first is OpenDyslexic, which was developed by my friend Abelardo Gonzalez (blog | Twitter) and is similar in concept to another typeface called Dyslexie. Dyslexie is proprietary, meaning that you need a license to use it1In fact, many typefaces we use day-to-day are proprietary, meaning that if you use them in a logo or poster design for instance, you may need to pay for the privilege.. OpenDyslexic is open-source and free to use.

Although research is divided as to whether fonts like these aid in helping dyslexic people read better, there is evidence that they may help with avoiding dyslexic-related errors. As it happens, Comic Sans is one of the British Dyslexia Association’s recommended choices for ease of legibility.

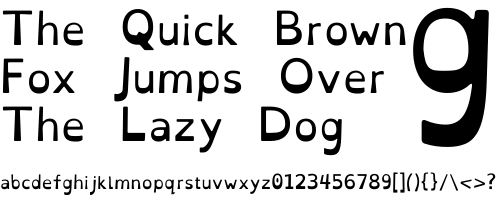

The second typeface, which despite being fairly new to me I like a whole lot for general use. It’s called Atkinson Hyperlegible, and it was shared with me by my own editor. What makes this one different is that its goal is distinctive character design, “to increase character recognition, ultimately improving readability.” Best of all, it’s free, and you can grab it from the Braille Institute’s website.

I’ll leave you with another font I like for writing code: Cascadia Code from a small company called Microsoft. You can get it from their GitHub page.

Definitely check these out and share your own favourite fonts in the comments below.