Although I don’t write about it much on this website, I am on the autism spectrum, and I have ADHD. I need to sit at the front of a room because it helps me see and hear better as there are fewer distractions. Venues don’t really need to make accommodations for me as long as I show up early enough and get a good seat. I don’t need special parking and I can mostly walk by myself without falling over.

I also have a really neat thing where my right hand stops working properly from time to time, and I can’t grasp or carry things without a lot of effort. Since I am left-handed, I’ve been fortunate that my dominant hand is able to accommodate for weakness in my right hand when this happens.

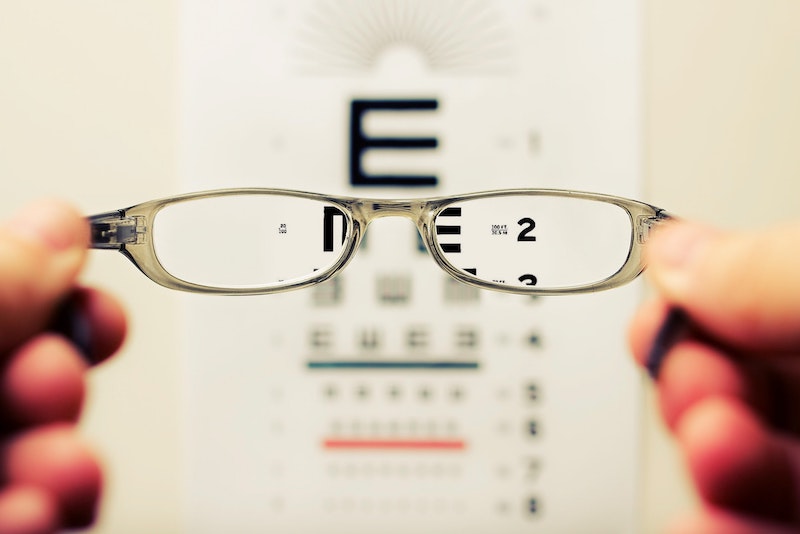

If you’ve met me personally (or looked at my purple avatar on the right-hand side of this page) you know I wear glasses. I have astigmatism so my corrective lenses not only help to make things clearer, but also correct how straight lines look.

Mentioning these things isn’t attention seeking behaviour on my part. Rather, it’s to highlight that while many of us consider ourselves able-bodied and mentally capable, many of us also do in fact need accommodations for accessibility, even if they seem insignificant, and the level of accommodation we need can change on a moment’s notice.

Imagine relying on glasses. How much you would be able to see if they broke on the first day of a week-long training workshop? What if they break and you have to drive somewhere?

Imagine not being able to take notes because your pen keeps falling out of your hand.

Imagine that you can walk just fine 99% of the time, but 1% of the time your knee locks up or your hip pops out. How about if you injure yourself and need to use crutches or a wheelchair while your body heals?

There is no practical difference in the accommodations required for physically disabled people who use a wheelchair to get around, and you who broke your foot and can’t walk on it for six weeks. This is the great irony of our world: people only think about this when it affects them directly.

Disabled people with chronic disabilities — whether they affect vision, hearing, physical movement or concentration, for example — need accommodations in the same way that I need to wear glasses.

But beware of your preconceptions. Some wheelchair users will tell you how freeing it is to be mobile, to be able to get around in one. Some Deaf people will tell you how nice it is if you just speak clearly so they can lip read. For those people who use sign language, they appreciate it if you can do the same, but not all Deaf people sign. Some Deaf people have technology implants to help them hear, so what you don’t want to do is raise your voice. You might think you’re helping, but technology has kept up with the times.

I had a family member who was legally blind because of detached retinas. She had a white cane and couldn’t see the edge of the sidewalk, but she also had an unerring ability to know where she was on the road even though she wasn’t allowed to drive. A building’s familiar silhouette doesn’t require perfect eyesight.

The thing about disabilities that a lot of able-bodied folks don’t seem to understand or appreciate, is that there is a spectrum, and we can all have bad days where things are worse. And for that matter, just because someone is in a wheelchair doesn’t mean they can’t walk. A blind person might be able to read a book with the right lenses. A Deaf person might be able to hear certain frequencies or hear if there’s no background noise. An autistic person can look and sound “normal” but may need some downtime in a dark and quiet space to recharge.

The point is, we shouldn’t make assumptions. We need to ask, and then we make accommodations where we can. Accessibility in this context literally means providing equitable access to content, materials, training, and to be inclusive of the diverse people in our community.

Additionally, we shouldn’t have to see a disability before accommodating for it, nor should we create awkward situations where individuals are pressured to “out themselves.” We should build accommodation into our workflow. We should build it into our physical spaces. The funny thing is that able-bodied people benefit from accommodations made for disabled people, so there’s no reason not to. When you’re older and unable to walk up stairs anymore, you’ll be grateful for the elevator or ramp.

There’s a very good chance that someone in your user group would benefit from you making your presentations more accessible even if they don’t ask. And, by making the accommodations for them, everyone else benefits. For example, I wrote about adding captions to video recordings a few weeks ago. Now when sighted people review my videos later, they can do so without audio and read a lot faster than listening to the session.

Photo by David Travis on Unsplash.

This has all to do with metaphorical blindness, as in, ‘Gosh, I never taught of that!’, and not actually to test your product on anything but a small, unrepresentative sample.

• When I lived in Dublin, the cyclepaths were awful (and frequently unused), presumably because the person who designed them drove a car and not a bike;

• Now that I am in my fifties, I realise how design choices make glasses an absolute necessity for people like me, presumably because the person who designed it was in their twenties and has super sharp eyesight. Maybe if the designer had had glasses, they would have realised that a bigger font size would have worked just as well and meant that fewer people would need to wear glasses as a consequence.

• When I go grocery shopping I need a magnifying glass to read the 4-point orange text on an yellow background and I curse whichever manager it was who ordered that deliberate obfuscation;

• When I was a parent of babies & toddlers and used a pram/pushchair, I learnt how unfriendly the environment is for people in wheelchairs and for mothers-to-be in their final trimester who are also pushing prams. I *can* lift the pram with child strapped inside up a flight of stairs or over the inconvenient handrail in the middle of the entrance of a bus or train but a heavily pregnant woman can’t and shouldn’t. Presumably the person who designed these handrails had never been pregnant;

• It is nice when trains have ground access for prams & wheelchairs but you need to know where they are. Some trains can be very long (12-16 carriages) and you don’t want to have to run many hundreds of meters to get the right door when you are in a wheelchair, have small children in tow and/or are heavily pregnant. Presumably the people who run the railway companies have never been in this position;

• The list goes on and on and on.

Comments are closed.